The Second Epistle to the Corinthians is the most personal, emotional, and autobiographical of all Paul’s letters. While 1 Corinthians was a practical manual correcting church behavior, 2 Corinthians is a raw defense of Paul’s own ministry and heart. Written to a church that had been swayed by flashy “super-apostles” who mocked Paul’s suffering and unimpressive presence, this letter completely flips the world’s definition of power upside down. Paul argues that true spiritual authority is not demonstrated by strength, eloquence, or success, but by weakness, suffering, and endurance. It creates a profound theology of the “Cross-centered life,” proving that God’s power is made perfect in human weakness.

Quick Facts

- Author: The Apostle Paul (and Timothy)

- Date Written: ~55–56 AD (about a year after 1 Corinthians)

- Location: Written from Macedonia (likely Philippi)

- Audience: The Church in Corinth and saints in Achaia

- Theme: Strength in Weakness / Defense of Apostolic Authority

- Key Word: “Comfort” (paraklesis) and “Ministry” (diakonia)

- Key Verse: 2 Corinthians 12:9 (“My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.”)

- Structure: Defense of Ministry (1–7) → The Collection (8–9) → Defense of Authority (10–13)

- Symbol: Jars of Clay — representing the fragile human vessel containing the glory of God

Title / Purpose

Title: The Second Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians (Second Corinthians).

Purpose:

- Vindication: To defend his apostolic authority against false teachers (“super-apostles”) who were questioning his credentials and leadership.

- Reconciliation: To express joy that the “painful letter” (a lost letter sent between 1 and 2 Corinthians) had led the church to repentance.

- Preparation: To prepare the Corinthians for his upcoming third visit and encourage them to complete their financial offering for the poor in Jerusalem.

Authorship & Context

The Author: Paul writes not as a distant theologian but as a wounded father. His tone shifts rapidly between deep affection, biting sarcasm, and profound vulnerability.

The Context: Relationships were rocky. After sending 1 Corinthians, Paul made a “painful visit” to them which went poorly. He then sent a “severe letter” (now lost) via Titus. 2 Corinthians is written after Titus returns with the good news that the majority of the church has repented and reaffirmed their loyalty to Paul, though a rebellious minority remains.

The Rivals: The “super-apostles” were likely Jewish Christian traveling preachers who were eloquent, charismatic, and demanded payment—everything Paul was not. They claimed Paul was weak and fickle.

Structure / Narrative Arc

The letter is often viewed in three distinct sections, moving from explanation to exhortation to confrontation.

1. Paul’s Defense of His Ministry (Chapters 1–7): Paul explains his recent travel changes (he wasn’t being fickle) and defines the nature of true Christian ministry. He contrasts the Old Covenant (fading glory) with the New Covenant (increasing glory). He famously describes ministry as “treasure in jars of clay” to show that the power comes from God, not the messenger.

2. The Collection for the Saints (Chapters 8–9): Paul gently pressures Corinth to finish the offering they promised for the poor in Jerusalem. He uses the example of the impoverished Macedonian churches who gave generously and sets out the principle of the “cheerful giver.”

3. Paul’s Defense of His Authority (Chapters 10–13): The tone shifts dramatically. Paul confronts the “super-apostles” directly. He engages in “foolish boasting,” listing his credentials—not his degrees or miracles, but his beatings, shipwrecks, and anxieties. He reveals his “thorn in the flesh” to prove that his weakness is the platform for God’s grace.

Major Themes

The Theology of Weakness: This is the heart of the book. The world admires strength, success, and charisma. Paul argues that God’s power is best displayed in human frailty. “When I am weak, then I am strong.”

Comfort in Suffering: The book opens with God as the “Father of compassion and God of all comfort,” teaching that we suffer so that we may comfort others with the comfort we have received.

Reconciliation: Not only reconciliation between Paul and the church, but the cosmic reconciliation of humanity to God. “God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ… and he has committed to us the message of reconciliation.”

Generosity: Giving is a response to grace. Jesus “became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich” (8:9).

Key Characters

Paul: The suffering servant, vulnerable and transparent. Titus: The peacemaker and courier who brought news of the Corinthians’ repentance. The “Super-Apostles”: The unnamed antagonists; charismatic false teachers who boasted of their Jewish pedigree and rhetorical skill. The Man in Christ (Paul): Paul refers to himself in the third person when describing his vision of the “third heaven” to avoid pride.

Notable Passages

Comfort (1:3–4): “Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ… who comforts us in all our troubles.”

Jars of Clay (4:7): “But we have this treasure in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us.”

New Creation (5:17): “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come: The old has gone, the new is here!”

The Unequally Yoked (6:14): “Do not be yoked together with unbelievers.”

The Cheerful Giver (9:7): “Each of you should give what you have decided in your heart to give… for God loves a cheerful giver.”

The Thorn in the Flesh (12:7–9): Paul pleads three times for the thorn to be removed. God answers: “My grace is sufficient for you.”

Legacy & Impact

Pastoral Care: This letter is the primary biblical resource for “theology of suffering.” It has comforted countless believers facing chronic pain, depression, or persecution by reframing suffering as a means of grace rather than a sign of God’s absence.

Christian Leadership: It redefines leadership from “power over” to “service under.” It warns the church against being seduced by charismatic personalities who lack the character of the Cross.

Fundraising: Chapters 8 and 9 remain the foundational text for Christian stewardship and charitable giving.

Symbolism / Typology

The Veil: Paul uses the image of Moses wearing a veil (Exodus 34) to symbolize the blindness of the Old Covenant. In Christ, the veil is removed, allowing believers to behold God’s glory with “unveiled faces.”

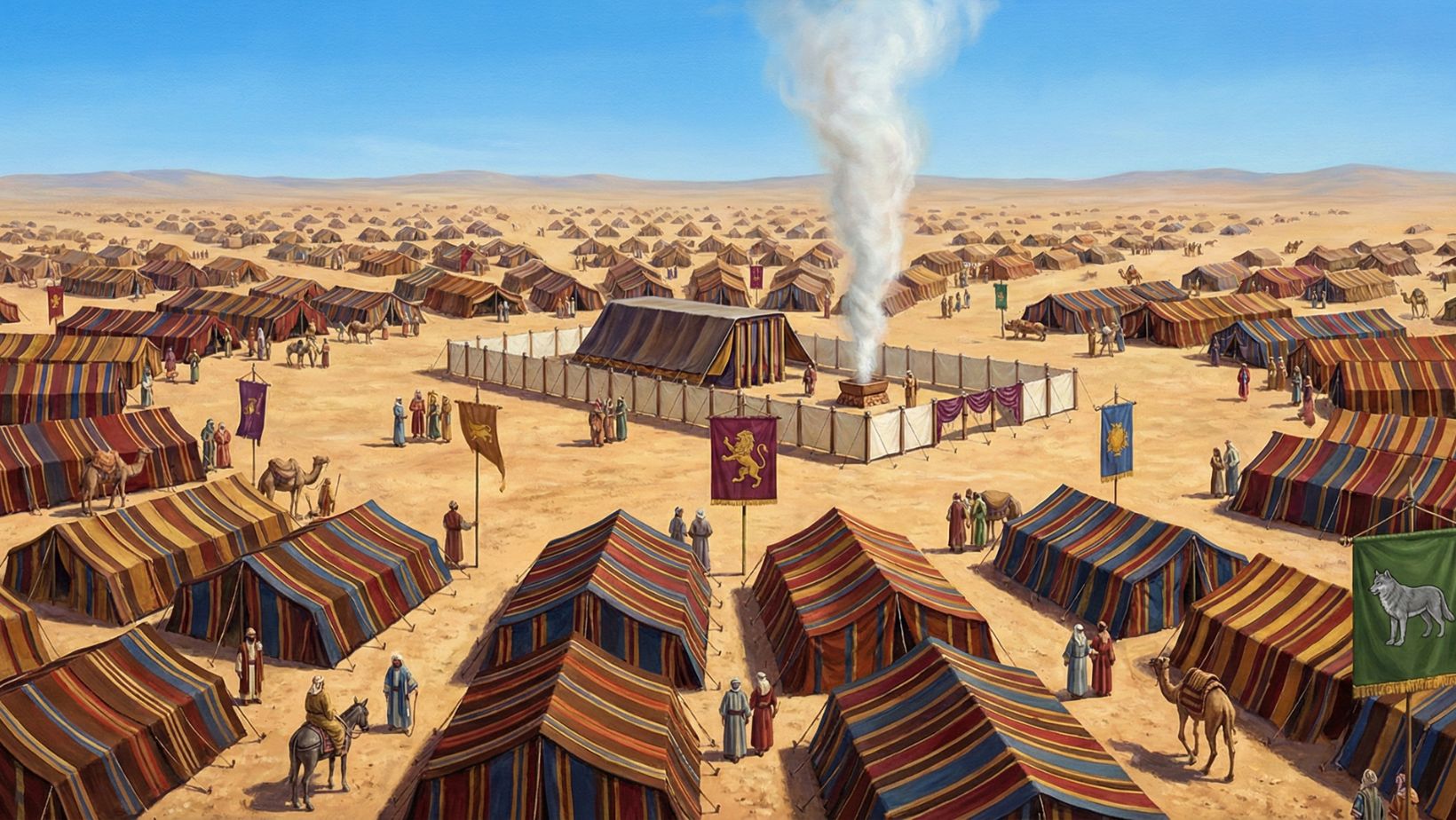

The Tent: Paul compares the earthly body to a temporary “tent” that is groaning and breaking down, contrasted with the permanent “building from God” (resurrection body) awaiting us in heaven (Chapter 5).

The Aroma: Believers are described as the “pleasing aroma of Christ”—a smell of life to those being saved, but the smell of death to those perishing.

Leave a Reply