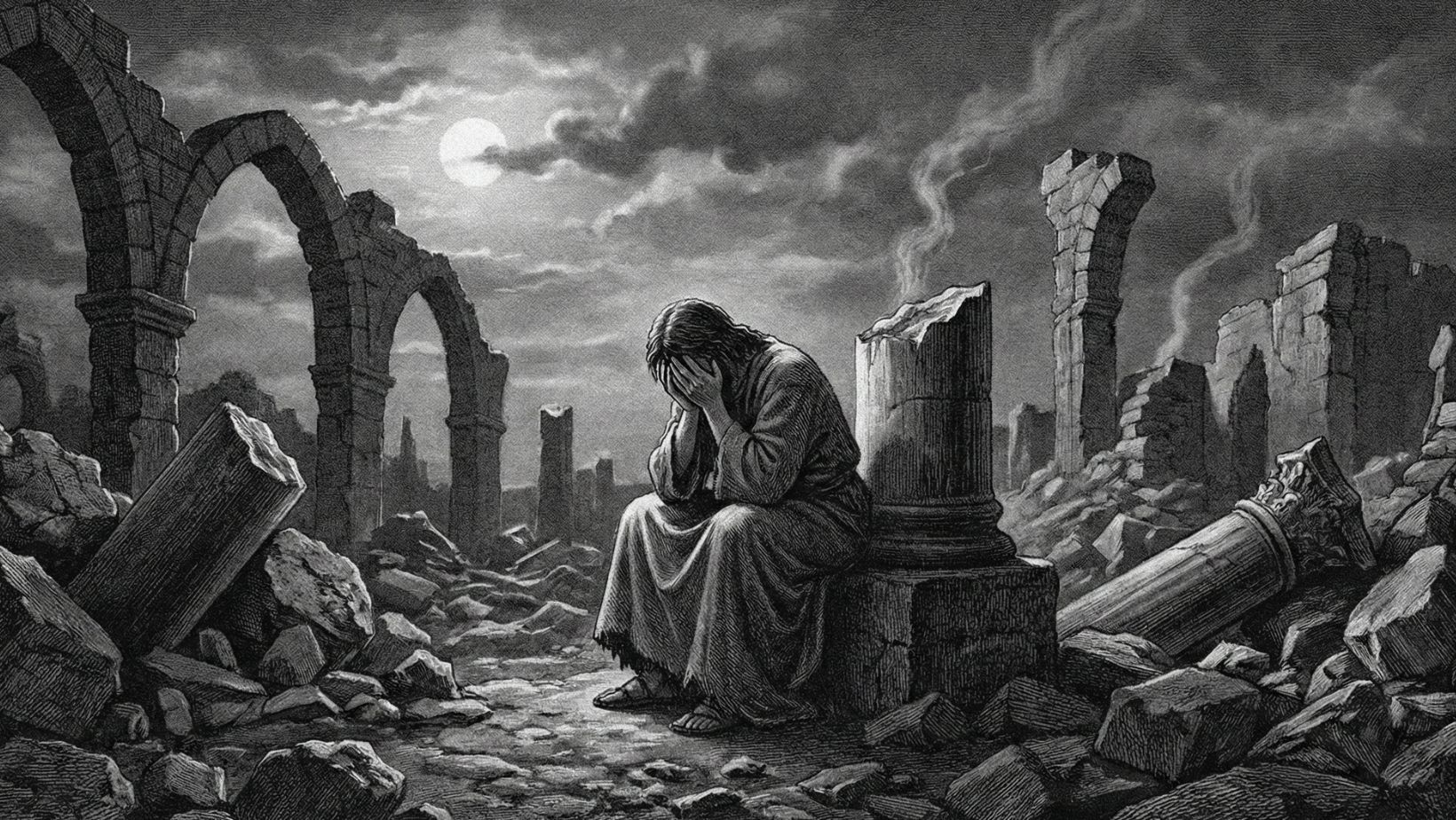

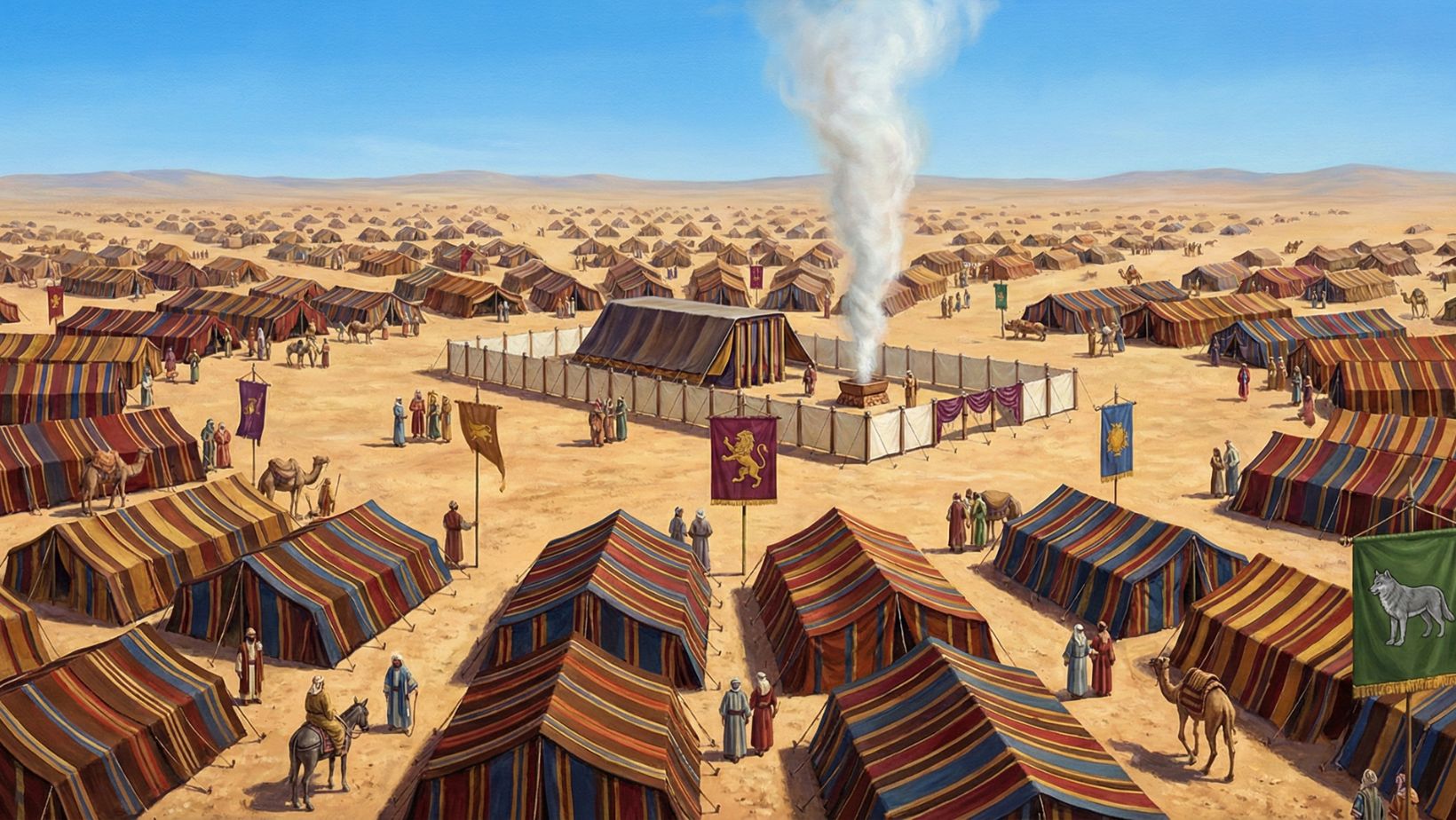

Lamentations is a collection of five desperate, poetic dirges (funeral songs) mourning the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 586 BCE. Traditionally attributed to Jeremiah, who sat weeping over the smoking ruins of the city he tried to save, the book is a raw, unfiltered expression of human grief. It does not offer easy answers or quick fixes; instead, it provides a sacred space for processing trauma. Uniquely, the book is highly structured—written as a series of acrostic poems based on the Hebrew alphabet—suggesting an attempt to impose order and meaning upon a chaotic and senseless tragedy. It stands as a testament that even in the midst of total abandonment, the believer can still talk to God, even if only to complain.

Quick Facts

- Name: Lamentations (Hebrew: Eikhah, meaning “How”)

- Author: Traditionally Jeremiah (The Septuagint prefaces it with “Jeremiah sat weeping…”)

- Date Written: Shortly after 586 BCE

- Structure: Five poems; four are acrostics (alphabetical order)

- Core Themes: Grief, divine judgment, hope in God’s faithfulness, corporate confession

- Setting: The ruins of Jerusalem immediately after the Babylonian conquest

- Literary Style: Qinah (funeral rhythm) and Acrostic poetry

- Key Symbol: The Lonely Widow — personifying the once-great city of Jerusalem

Name Meaning

The Hebrew title Eikhah (“How”) is the opening word of chapters 1, 2, and 4. It is an exclamation of shock and horror: “How could this happen?” “How does the city sit so lonely?” The English title comes from the Latin Lamentationes, meaning loud wailing or weeping.

Historical Context

Time: The book takes place in the immediate aftermath of the Siege of Jerusalem. The city has fallen, the King is captured, the Temple is burned, and the people are starving or dead. The Reality: The descriptions are graphic and eyewitness-based. It describes mothers eating their children due to starvation, princes hanged by their hands, and priests murdered in the sanctuary. The Theology: The book accepts that this destruction is not an accident, but the direct result of God keeping His promise to punish covenant betrayal.

Literary Structure

The book’s structure is its most fascinating feature. Chapters 1, 2, and 4 are perfect acrostics—each verse begins with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet (Aleph, Bet, Gimel, etc.). Chapter 3 (the climax) is a triple acrostic, with three verses for each letter. This structure serves a purpose: it covers the A-to-Z of suffering, ensuring that the grief is fully expressed, yet contained within a boundary so the sorrow doesn’t go on forever.

Major Roles / Identity

Lady Jerusalem (The Daughter of Zion): The city is personified as a humiliated widow, weeping in the night with no one to comfort her. She stretches out her hands, begging for mercy. The Suffering Man: In Chapter 3, a representative individual (likely Jeremiah) steps forward to speak for the nation: “I am the man who has seen affliction by the rod of his wrath.” The Enemy: Shockingly, the enemy in the poem is often God Himself. The poet describes God as a bear lying in wait, an archer targeting his own people. The Mockers: The surrounding nations who clap their hands and hiss at Jerusalem’s downfall.

Key Character Traits

Honesty: The book does not hide the gruesome details of the siege. It forces the reader to look at the consequences of sin. Submission: “Let him bury his face in the dust—there may yet be hope.” The poet accepts the yoke of discipline. Community: Suffering is not private; it is a communal experience requiring a collective cry to God.

Main Events / Chapters

Chapter 1: The Widow’s Grief: Describes the desolation of the city. “How lonely sits the city that was full of people!” Chapter 2: The Lord’s Anger: A brutal description of God destroying His own temple and altar. “The Lord has become like an enemy.” Chapter 3: The Pivot: The center of the book. The narrator hits rock bottom but then remembers God’s character. This contains the theological core of the book. Chapter 4: The Siege recounted: Contrasts the former glory of Jerusalem’s gold and princes with their current blackened, starving state. Chapter 5: The Prayer: The acrostic structure breaks down. It is a chaotic, final plea for restoration: “Restore us to yourself, O Lord, that we may return.”

Notable Passages

Lamentations 3:22–23: The beacon of light: “Because of the Lord’s great love we are not consumed, for his compassions never fail. They are new every morning; great is your faithfulness.” Lamentations 3:24: The confession: “I say to myself, ‘The Lord is my portion; therefore I will wait for him.’” Lamentations 5:21: The ending plea: “Restore us to you, Lord, so that we may return; renew our days as of old.”

Legacy & Impact

Lamentations is read annually by Jews on Tisha B’Av, the fast day commemorating the destruction of both the First and Second Temples. It teaches the church the language of lament—proving that faith is not always “happy,” and that complaining to God is a valid form of worship when done in trust.

Symbolism / Typology

The Yoke: Mentioned in Chapter 3 (“It is good for a man to bear the yoke while he is young”), symbolizing submission to God’s difficult will. The Cup of Wrath: Edom is warned that the cup of judgment that Jerusalem drank will eventually be passed to them. The Dust: Sitting in the dust symbolizes humiliation and the death of national pride.

Leave a Reply