1 Samuel 1 opens with the domestic drama of a pious but divided household in the hill country of Ephraim. It introduces Elkanah, a devoted man with two wives: Peninnah, who is fruitful but cruel, and Hannah, who is barren but beloved. The narrative focuses on Hannah’s deep anguish over her infertility, exacerbated by her rival’s taunts during their annual pilgrimage to Shiloh. In her desperation, Hannah prays fervently at the Tabernacle, vowing to dedicate her son to the Lord if He grants her one. Misunderstood by the high priest Eli as being drunk, she defends her integrity, receiving his blessing. God answers her prayer, and she conceives Samuel. True to her vow, after weaning him, she makes the ultimate sacrifice: bringing her young son to Shiloh to serve God permanently, transitioning from the private sorrow of a barren woman to the public deliverance of Israel through her son, the future prophet.

1. The Broken Home and the Annual Pilgrimage (1 Samuel 1:1–8)

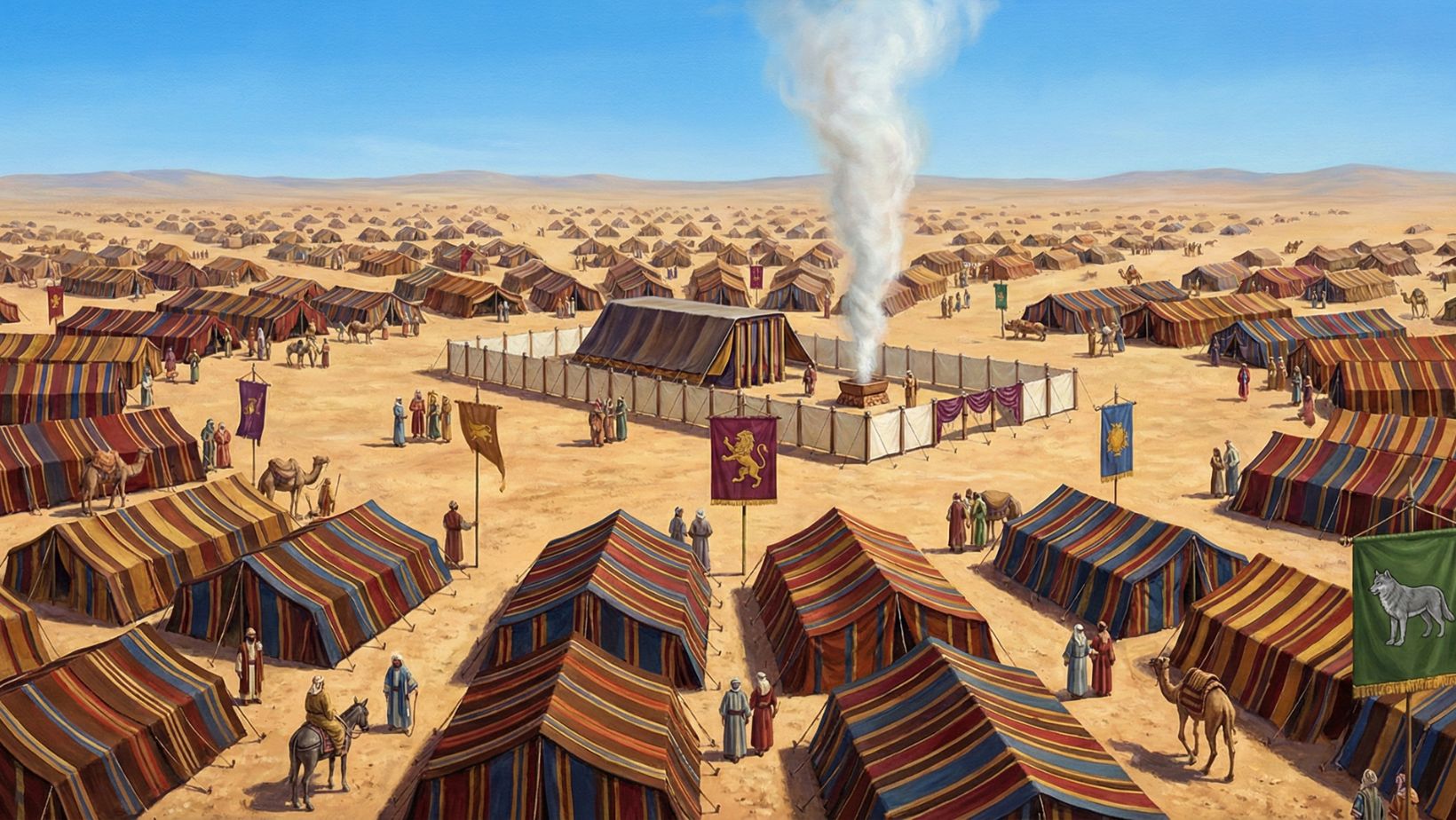

1 There was a man named Elkanah who lived in Ramah in the region of Zuph in the hill country of Ephraim. He was the son of Jeroham, son of Elihu, son of Tohu, son of Zuph, of Ephraim. 2 Elkanah had two wives, Hannah and Peninnah. Peninnah had children, but Hannah did not. 3 Each year Elkanah would travel to Shiloh to worship and sacrifice to the Lord of Heaven’s Armies at the Tabernacle. The priests of the Lord at that time were the two sons of Eli—Hophni and Phinehas. 4 On the days Elkanah presented his sacrifice, he would give portions of the meat to Peninnah and each of her children. 5 And though he loved Hannah, he would give her only one choice portion because the Lord had given her no children. 6 So Peninnah would taunt Hannah and make fun of her because the Lord had kept her from having children. 7 Year after year it was the same—Peninnah would taunt Hannah as they went to the Tabernacle. Each time, Hannah would be reduced to tears and would not even eat. 8 “Why are you crying, Hannah?” Elkanah would ask. “Why aren’t you eating? Why be downhearted just because you have no children? You have me—isn’t that better than having ten sons?”

Commentary:

- Genealogy and Setting (v. 1): The detailed genealogy establishes Elkanah’s respectable lineage. Though identified here with Ephraim (geographically), 1 Chronicles 6:16-30 identifies Samuel’s line as Levites. This suggests Elkanah was a Levite living in Ephraimite territory, explaining Samuel’s later priestly functions.

- Polygamy and Tension (v. 2): The text presents polygamy without explicit condemnation but vividly illustrates its negative consequences. The domestic structure mirrors the tension between Sarah and Hagar or Rachel and Leah. “Hannah” means grace or favor, while “Peninnah” means pearl or coral.

- Shiloh and the Priesthood (v. 3): Shiloh was the religious center of Israel before Jerusalem, housing the Ark of the Covenant. The mention of Hophni and Phinehas foreshadows the corruption of the priesthood, which Samuel will eventually replace.

- Lord of Heaven’s Armies (v. 3): This is the first occurrence in the Bible of the title Yahweh Sabaoth (Lord of Hosts/Armies). It emphasizes God’s sovereign power over all earthly and cosmic forces, a fitting title for Hannah to invoke in her helplessness.

- The Closed Womb (v. 5): The text explicitly states “the Lord had given her no children” (literally: the Lord had closed her womb). This theological assertion places the sovereignty of life and death in God’s hands, setting the stage for a miraculous intervention.

- Provocation (v. 6–7): Peninnah is described as a “rival” (Hebrew tsarah, meaning adversary or tight place). She uses the sacred festival—a time intended for joy and thanksgiving—as a weapon of psychological torment against Hannah.

- Elkanah’s Well-Meaning Ignorance (v. 8): Elkanah loves Hannah but fails to understand her pain. His question, “Isn’t that better than having ten sons?” highlights the cultural disconnect. In the ancient Near East, a woman’s social security, identity, and theological standing were tied to childbearing. His love provided emotional comfort but not social or spiritual restoration.

2. The Vow and the Misunderstanding (1 Samuel 1:9–18)

9 Once after a sacrificial meal at Shiloh, Hannah got up and went to pray. Eli the priest was sitting at his customary place beside the entrance of the Tabernacle. 10 Hannah was in deep anguish, crying bitterly as she prayed to the Lord. 11 And she made this vow: “O Lord of Heaven’s Armies, if you will look upon my sorrow and answer my prayer and give me a son, then I will give him back to you. He will be yours for his entire lifetime, and as a sign that he has been dedicated to the Lord, his hair will never be cut.” 12 As she was praying to the Lord, Eli watched her. 13 Seeing her lips moving but hearing no sound, he thought she had been drinking. 14 “Must you come here drunk?” he demanded. “Throw away your wine!” 15 “Oh no, sir!” she replied. “I haven’t been drinking wine or anything stronger. But I am very discouraged, and I was pouring out my heart to the Lord. 16 Don’t think I am a wicked woman! For I have been praying out of great anguish and sorrow.” 17 “In that case,” Eli said, “go in peace! May the God of Israel grant the request you have asked of him.” 18 “Oh, thank you, sir!” she exclaimed. Then she went back and began to eat again, and she was no longer sad.

Commentary:

- Silent Prayer (v. 12–13): Hannah prays in her heart, moving only her lips. In ancient religious practice, silent prayer was uncommon; prayers were usually audible. This partly explains Eli’s confusion, but it also highlights his lack of spiritual discernment.

- The Nazirite Vow (v. 11): Hannah vows to dedicate her son as a Nazirite (Numbers 6). The condition “his hair will never be cut” is a specific mark of this consecration. Samson is the only other lifelong Nazirite mentioned explicitly from birth (Judges 13:5). Hannah is offering to give up the very thing she desires most—raising a son—for God’s service.

- Eli’s Accusation (v. 14): Eli, the high priest, represents the spiritual dullness of the era. He sits “by the doorpost” (a position of passivity) and is quick to judge a pious woman as a drunkard. This reflects the moral decay of the priesthood, where drunken behavior at the shrine was perhaps not uncommon.

- Hannah’s Defense (v. 15–16): Hannah responds with immense grace and respect (“Oh no, sir!”). She describes her prayer as “pouring out my heart”—a fluid metaphor for emptying oneself of grief before God.

- The Blessing (v. 17): Eli realizes his error and pronounces a blessing. Though he does not know the content of her prayer, his office as High Priest carries weight. He acts as a conduit for God’s peace.

- Faith in Action (v. 18): The change in Hannah is immediate. Before she has conceived, simply having “poured out” her burden and received the priestly blessing restores her appetite and countenance. Faith changes her disposition before the circumstance changes.

3. The Birth of Samuel (1 Samuel 1:19–20)

19 The entire family got up early the next morning and went to worship the Lord once more. Then they returned home to Ramah. When Elkanah slept with Hannah, the Lord remembered her plea; 20 and in due time she gave birth to a son. She named him Samuel, for she said, “I asked the Lord for him.”

Commentary:

- Divine Remembrance (v. 19): The phrase “the Lord remembered her” is covenantal language. It does not imply God had forgotten, but that He was now moving to act on her behalf (similar to Noah in Gen 8:1 and Rachel in Gen 30:22).

- Naming Samuel (v. 20): The etymology of “Samuel” (Hebrew Shemuel) is debated. It sounds like the Hebrew for “heard by God” (Shama-El) or “name of God” (Shem-El). Hannah explains the name with a sound-alike phrase “asked of the Lord” (sha’al), linking his identity permanently to prayer.

4. The Dedication (1 Samuel 1:21–28)

21 The next year Elkanah and his family went on their annual trip to offer a sacrifice to the Lord. 22 But Hannah did not go. She told her husband, “Wait until the boy is weaned. Then I will take him to the Tabernacle and leave him there with the Lord permanently.” 23 “Whatever you think is best,” Elkanah agreed. “Stay here for now, and may the Lord help you keep your promise.” So she stayed home and nursed the boy until he was weaned. 24 When the child was weaned, Hannah took him to the Tabernacle in Shiloh. They brought along a three-year-old bull for the sacrifice and a basket of flour and some wine. 25 After sacrificing the bull, they brought the boy to Eli. 26 “Sir, do you remember me?” Hannah asked. “I am the very woman who stood here several years ago praying to the Lord. 27 I asked the Lord to give me this boy, and he has granted my request. 28 Now I am giving him to the Lord, and he will belong to the Lord his whole life.” And they worshiped the Lord there.

Commentary:

- Delaying the Vow (v. 22): Hannah stays home to nurse Samuel. In that culture, weaning could take 2–3 years. This period allows her to pour a lifetime of motherly affection into the short time she has with him.

- Elkanah’s Support (v. 23): Elkanah affirms her decision, showing that the vow, though made by Hannah, is supported by the head of the household (a legal necessity for vows in Num 30).

- The Costly Sacrifice (v. 24): The offering is generous: a three-year-old bull (or three bulls, depending on translation manuscripts), an ephah of flour, and wine. This indicates both gratitude and perhaps the wealth of Elkanah, but primarily the weight of the occasion.

- “Lending” to the Lord (v. 28): The Hebrew wordplay continues. Hannah says, “I am giving him” (Hebrew hishiltihu, related to sha’al – to ask/lend). Because she “asked” for him, she now “lends/dedicates” him back. It is a reciprocal transaction of grace.

- Worship (v. 28): The chapter ends with worship. The focus shifts from the gift (Samuel) to the Giver (Yahweh). Hannah does not leave weeping as she did in verse 10; she leaves worshiping.

Theological Significance of 1 Samuel 1

- The Reversal of Fortunes: This chapter introduces a major theme of 1 & 2 Samuel—God exalts the humble and humbles the proud. The barren woman becomes the mother of the prophet who will anoint kings, while the fruitful rival fades into obscurity.

- Prayer as the Engine of History: The political and spiritual reformation of Israel (the transition from Judges to Monarchy) begins not with a battle or a decree, but with the desperate prayer of a suffering woman.

- God’s Sovereignty over Life: The narrative reinforces that children and life are gifts from God. He opens and closes the womb to serve His redemptive purposes.

- Faithfulness in Stewardship: Hannah models ultimate stewardship. She recognizes that the best place for her greatest treasure is in God’s hands, even if it means separation.

Practical Applications

- Pouring Out the Heart: We learn from Hannah that authentic prayer involves honest emotional expression. We can bring our bitterness, anguish, and tears to God.

- Dealing with Provocation: Hannah did not retaliate against Peninnah. She took her pain to the Lord rather than fighting back, modeling spiritual maturity.

- Keeping Vows: It is easy to make promises to God in times of crisis and forget them in times of comfort. Hannah models integrity by following through at great personal cost.

- Misunderstanding by Leaders: Even spiritual leaders (like Eli) can misjudge us. Hannah shows us how to respond with respect and truth rather than offense.

Final Insight

1 Samuel 1 is a testament to the power of a “helpless” person. Hannah had no political power, no social standing as a barren woman, and no support from the priesthood. Yet, through prayer, she became the instrument God used to birth the future of the nation. Her empty womb became the cradle of Israel’s hope.

Leave a Reply