Genesis 50 serves as the epilogue to the Patriarchal Age and the bridge to the book of Exodus. The chapter is dominated by two major themes: the honor paid to the past and the hope for the future. It details the magnificent state funeral of Jacob, where Egyptian royalty and Hebrew shepherds unite to mourn a great man, fulfilling his wish to be buried in the Promised Land. The narrative then addresses the lingering guilt of Joseph’s brothers, who fear retribution now that their father is dead. Joseph responds with the theological summit of the book, declaring that human evil and divine good can operate simultaneously. The book concludes with the death of Joseph, who, rather than building a monument in Egypt, leaves instructions for his bones to be carried to Canaan, predicting the future Exodus.

1. The Great Mourning and Burial (Genesis 50:1–14 NLT)

1 Joseph threw himself on his father and wept over him and kissed him. 2 Then Joseph told the physicians who served him to embalm his father’s body; so Jacob was embalmed. 3 The embalming process took forty days, and there was a period of national mourning for seventy days. 4 When the period of mourning was over, Joseph approached Pharaoh’s advisers and said, “Please do me this favor and speak to Pharaoh on my behalf. 5 Tell him that my father made me swear an oath. He said to me, ‘Listen, I am about to die. Take my body back to the land of Canaan, and bury me in the tomb I hewed out for myself.’ So please allow me to go and bury my father. After that, I will return.” 6 Pharaoh agreed to Joseph’s request. “Go and bury your father, as he made you promise,” he said. 7 So Joseph went up to bury his father. He was accompanied by all of Pharaoh’s officials, all the senior members of Pharaoh’s household, and all the senior officers of Egypt. 8 Joseph also took his entire household and his brothers and their households. But they left their little children and flocks and herds in the land of Goshen. 9 A great number of chariots and charioteers accompanied Joseph. It was a huge funeral procession. 10 When they arrived at the threshing floor of Atad, near the Jordan River, they held a very great and solemn memorial service, with a seven-day period of mourning for Joseph’s father. 11 The local residents, the Canaanites, watched them mourning at the threshing floor of Atad. Then they said, “This is a deep mourning for these Egyptians.” So they called the place Abel-mizraim, which is near the Jordan River. 12 So Jacob’s sons did as he had commanded them. 13 They carried his body to the land of Canaan and buried him in the cave in the field of Machpelah, near Mamre. This is the cave that Abraham had bought as a permanent burial place from Ephron the Hittite. 14 After burying his father, Joseph returned to Egypt with his brothers and all who had accompanied him to his father’s burial.

Commentary:

- Egyptian Embalming (v. 2-3): Joseph orders “physicians” rather than priests to embalm Jacob. This avoids the pagan religious rituals usually associated with Egyptian mummification while preserving the body for the long journey.

- The Timeline: 40 days for embalming and 70 days of mourning. This was a royal treatment; typically, only Pharaohs received 72 days of mourning. It reflects Joseph’s immense standing in Egypt.

- Asking Permission (v. 4-5): Joseph does not speak to Pharaoh directly but goes through intermediaries (“Pharaoh’s advisers”). As a mourner, Joseph would have been unshaven and in mourning clothes, making him ritually unclean to enter the royal presence.

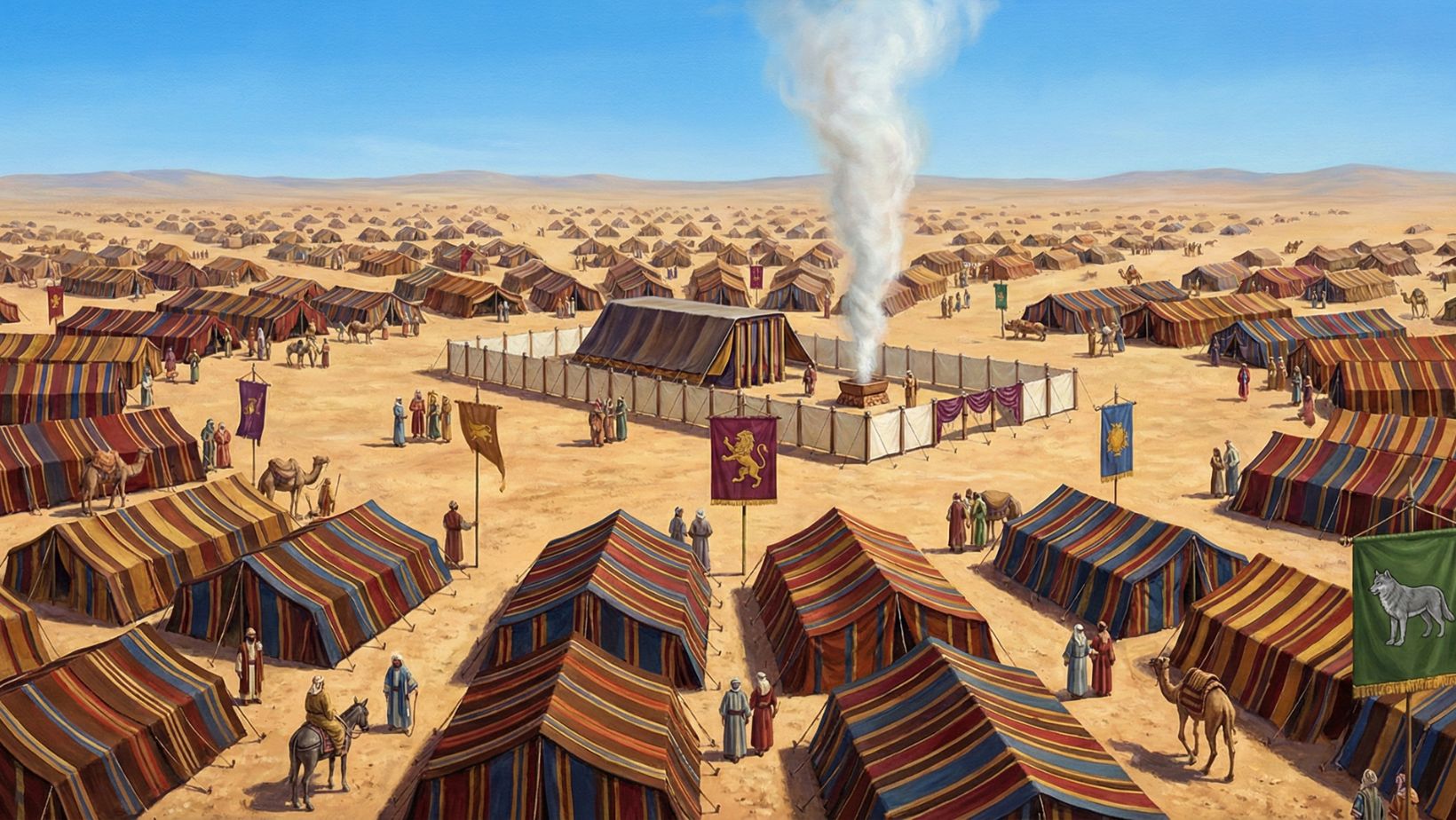

- The State Funeral (v. 7-9): The procession is staggering. It includes the entire Hebrew clan (except children) and the military and political elite of Egypt (“chariots and charioteers”). It is effectively an invasion of Canaan, but for mourning, not war.

- Abel-mizraim (v. 11): The Canaanites are shocked by the display of grief. They rename the place Abel-mizraim, a pun: Abel means “meadow,” but it sounds like Ebel, which means “mourning.” To the locals, it looked like “The Mourning of Egypt.”

- Fulfillment of the Oath (v. 13): Jacob is laid to rest with Abraham and Isaac. This act stakes a claim: despite their residence in Egypt, their roots and their future belong to Canaan.

2. The Theology of Providence (Genesis 50:15–21 NLT)

15 But now that their father was dead, Joseph’s brothers became fearful. “Now Joseph will show his anger and pay us back for all the wrong we did to him,” they said. 16 So they sent this message to Joseph: “Before your father died, he instructed us 17 to say to you: ‘Please forgive your brothers for the great wrong they did to you—for their sin in treating you so cruelly.’ So we, the servants of the God of your father, beg you to forgive our sin.” When Joseph received the message, he broke down and wept. 18 Then his brothers came and threw themselves down before him. “Look, we are your slaves!” they said. 19 But Joseph replied, “Don’t be afraid of me. Am I God, that I can punish you? 20 You intended to harm me, but God intended it all for good. He brought me to this position so I could save the lives of many people. 21 No, don’t be afraid. I will continue to take care of you and your children.” So he reassured them by speaking kindly to them.

Commentary:

- The Return of Fear (v. 15): A guilty conscience is hard to silence. The brothers assume Joseph’s kindness was merely out of respect for Jacob. Now that the “restrainer” (Jacob) is gone, they fear retaliation.

- The Fabricated Message (v. 16-17): It is widely believed by commentators that this message from Jacob was fabricated by the brothers out of fear. Jacob likely died knowing the family was reconciled and would not have felt the need for such a note.

- Joseph’s Tears (v. 17): Joseph weeps because he is misunderstood. He has loved them genuinely for 17 years, yet they still view him through the lens of their own sin. They see a judge; he sees himself as a brother.

- “Am I God?” (v. 19): Joseph renounces the right to vengeance. To seek revenge is to usurp God’s role as the Judge.

- The Great Paradox (v. 20): This is the thesis statement of Genesis.

- Human Intent: “You intended (chashav) to harm me.” Joseph does not whitewash their sin. It was evil.

- Divine Intent: “But God intended (chashav) it all for good.” God did not just react to their evil; He wove their evil into a plan for salvation.

- The Outcome: “To save the lives of many people.” The suffering of the one (Joseph) led to the salvation of the many.

- Comfort (v. 21): Joseph proves his forgiveness by promising continued economic support (“I will continue to take care of you”).

3. The Death of Joseph (Genesis 50:22–26 NLT)

22 So Joseph and his brothers and their families continued to live in Egypt. Joseph lived to the age of 110. 23 He lived to see three generations of descendants of his son Ephraim, and he lived to see the birth of the children of Manasseh’s son Machir, whom he claimed as his own. 24 “Soon I will die,” Joseph told his brothers, “but God will surely come to help you and lead you out of this land of Egypt. He will bring you back to the land he solemnly promised to give to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob.” 25 Then Joseph made the sons of Israel swear an oath, and he said, “When God comes to help you and lead you back, you must take my bones with you.” 26 So Joseph died at the age of 110. The Egyptians embalmed him, and his body was placed in a coffin in Egypt.

Commentary:

- 110 Years (v. 22): In ancient Egyptian culture, 110 years was considered the ideal lifespan—a sign of a life perfectly blessed and wise.

- Grandchildren on the Knees (v. 23): The phrase “whom he claimed as his own” (literally: were born upon Joseph’s knees) suggests an adoption ritual similar to Jacob’s adoption of Ephraim and Manasseh. Joseph lived to see the stability of his line.

- Prophecy of Exodus (v. 24): Joseph dies with the name of the Promised Land on his lips. “God will surely come to help you” (literally: visiting he will visit you). He predicts the Exodus centuries before it happens.

- The Oath of the Bones (v. 25): Joseph does not ask to be buried immediately in Canaan (like Jacob). He asks for his bones to accompany them when they leave.

- Significance: Joseph’s unburied coffin would remain in Egypt for hundreds of years as a silent sermon. Every time an Israelite saw it, they would be reminded: “We are not staying here. We are going home.”

- A Coffin in Egypt (v. 26): The book of Genesis begins with God creating the heavens and the earth (Life) and ends with a coffin in Egypt (Death). However, it is a death pregnant with hope. The coffin is not the end; it is a waiting room for the fulfillment of the promise.

Theological Significance of Genesis 50

- Concurrence (Compatibilism): Verse 20 teaches that two agents can cause the same event with different intentions. The brothers were 100% responsible for their sin, and God was 100% sovereign over the outcome. God does not just fix mistakes; He uses the malice of men to achieve His redemptive purposes.

- Type of Christ: Joseph’s refusal to condemn his brothers and his provision for them (“I will take care of you”) foreshadows Jesus, who, though rejected by His own, offers forgiveness and sustenance to those who betrayed Him.

- The Hope of Resurrection: The emphasis on burial in Canaan (for both Jacob and Joseph) signifies a refusal to accept Egypt (the world) as the final home. It is a proto-resurrection hope—desiring to be found in God’s land when the end comes.

Practical Applications

- Interpreting Life Backwards: We often cannot understand our suffering while we are in it (the pit/prison). Only looking back (Genesis 50) can we see the “good” God intended. We must trust God’s character in the dark.

- Forgiveness as Release: Forgiveness means giving up the right to punish (“Am I God?”). If we hold onto a grudge, we are trying to do God’s job.

- Legacy of Faith: Joseph left instructions for his bones. We should live (and prepare to die) in a way that points the next generation toward God’s promises. Our death should be a statement of our life’s trust.

Leave a Reply