Ruth 1 introduces a narrative of tragedy, loyalty, and divine providence set during the dark era of the Judges. It begins with a famine that drives an Israelite family—Elimelech, Naomi, and their two sons—from Bethlehem to Moab, a land of historic enemies. Tragedy strikes as the men of the family die, leaving Naomi a destitute widow in a foreign land with two Moabite daughters-in-law, Orpah and Ruth. Hearing that God has provided food for Israel, Naomi decides to return. While Orpah stays in Moab, Ruth makes a covenant-like commitment to stay with Naomi and serve Yahweh. The chapter concludes with their arrival in Bethlehem, where Naomi expresses her deep bitterness and emptiness, unaware that the barley harvest signifies a new beginning.

1. The Crisis: Famine and Death (Ruth 1:1–5 NLT)

1 In the days when the judges ruled in Israel, a severe famine came upon the land. So a man from Bethlehem in Judah left his home and went to live in the country of Moab, taking his wife and two sons with him. 2 The man’s name was Elimelech, and his wife was Naomi. Their two sons were Mahlon and Chilion. They were Ephrathites from Bethlehem in the land of Judah. And when they reached Moab, they settled there. 3 Then Elimelech died, and Naomi was left with her two sons. 4 The two sons married Moabite women. One married a woman named Orpah, and the other a woman named Ruth. But about ten years later, 5 both Mahlon and Chilion died. This left Naomi alone, without her two sons or her husband.

Commentary:

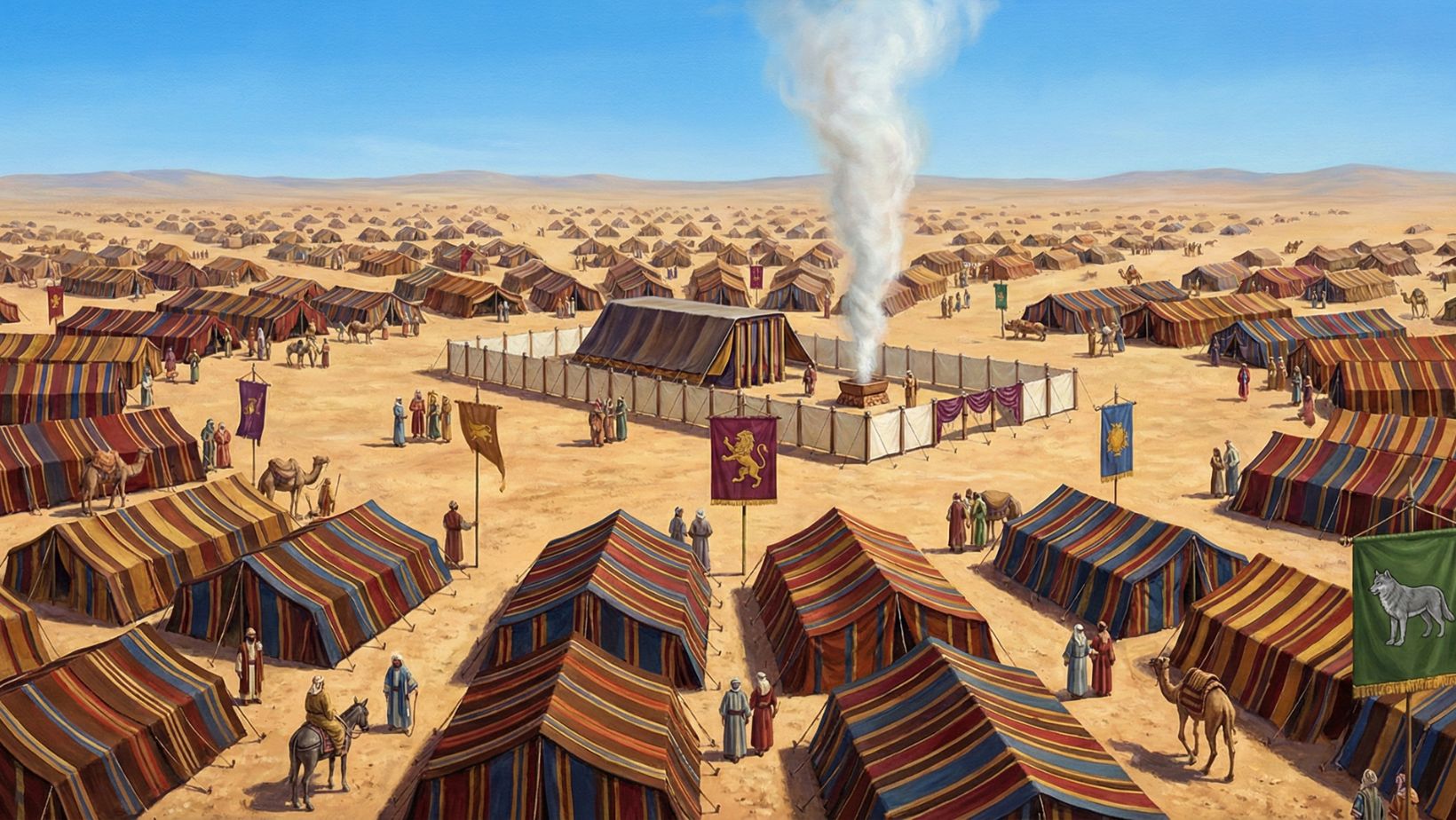

- Historical Context (v. 1): The phrase “In the days when the judges ruled” sets a bleak tone. This period (approx. 1375–1050 BC) was characterized by moral chaos, spiritual apostasy, and political instability (Judges 21:25).

- The Irony of Bethlehem (v. 1): Bethlehem translates to “House of Bread.” The narrative begins with a stark irony: there is no bread in the “House of Bread.”

- The Move to Moab (v. 1): Elimelech’s decision to move to Moab is significant. The Moabites were traditional enemies of Israel, descendants of Lot’s incestuous union (Genesis 19). Leaving the Promised Land for a pagan nation suggests a desperate survival instinct overtaking faith.

- Meaning of Names (v. 2):

- Intermarriage (v. 4): The sons marrying Moabite women was problematic. While not explicitly forbidden in the same way as Canaanite marriages, Deuteronomy 23:3 forbade Moabites from entering the assembly of the Lord.

- Total Destitution (v. 5): The death of all three men left Naomi in a perilous position. In the ancient Near East, a widow without sons had no legal standing, economic protection, or social security. She is stripped of her identity and support.

Insight: The story begins with the complete collapse of human support structures. Naomi loses her home, her husband, and her children, setting the stage for God to fill her emptiness in unexpected ways.

2. Naomi’s Decision to Return (Ruth 1:6–13 NLT)

6 Then Naomi heard in Moab that the Lord had blessed his people in Judah by giving them good crops again. So Naomi and her daughters-in-law got ready to leave Moab to return to her homeland. 7 With her two daughters-in-law she set out from the place where she had been living, and they took the road that would lead them back to Judah. 8 But on the way, Naomi said to her two daughters-in-law, “Go back to your mothers’ homes. And may the Lord reward you for your kindness to your husbands and to me. 9 May the Lord bless you with the security of another marriage.” Then she kissed them good-bye, and they all broke down and wept. 10 “No,” they said. “We want to go with you to your people.” 11 But Naomi replied, “Why should you go on with me? Can I still give birth to other sons who could grow up to be your husbands? 12 No, my daughters, return to your parents’ homes, for I am too old to marry again. And even if I were possible, and I were to get married tonight and bear sons, 13 then what? Would you wait for them to grow up and refuse to marry someone else? No, of course not, my daughters! Things are far more bitter for me than for you, because the Lord himself has raised his fist against me.”

Commentary:

- Divine Providence (v. 6): The famine ends not by chance, but because “the Lord had blessed his people.” God is the active agent in nature and sustenance.

- Naomi’s Selflessness (v. 8): Despite her grief, Naomi prioritizes the welfare of her daughters-in-law. She releases them from familial obligation.

- Prayer for Hesed (v. 8): Naomi prays that the Lord will show them “kindness.” The Hebrew word here is hesed—covenant loyalty or loyal love. She asks God to treat them with the same loyalty they showed the family.

- The Desire for Rest (v. 9): She wishes them “security” (Hebrew menuchah), referring to the stability and rest found in a husband’s home.

- The Levirate Law Argument (v. 11-13): Naomi references the custom where a brother marries his deceased brother’s widow to provide an heir (Deuteronomy 25:5–10). She argues logically: she has no more sons, and she is too old to bear them.

- Naomi’s Theology of Suffering (v. 13): Naomi interprets her suffering as divine antagonism. She states, “the Lord himself has raised his fist against me” (literally: the hand of the Lord has gone out against me). She acknowledges God’s power but questions His benevolence toward her.

Insight: Bitterness often stems from a correct belief in God’s sovereignty mixed with a limited view of His purposes. Naomi sees God’s hand as a fist striking her, not realizing it is a hand preparing to redeem her.

3. The Great Choice: Orpah Leaves, Ruth Clings (Ruth 1:14–18 NLT)

14 And again they wept together, and Orpah kissed her mother-in-law good-bye. But Ruth clung tightly to Naomi. 15 “Look,” Naomi said to her, “your sister-in-law has gone back to her people and to her gods. You should do the same.” 16 But Ruth replied, “Don’t ask me to leave you and turn back. Wherever you go, I will go; wherever you live, I will live. Your people will be my people, and your God will be my God. 17 Wherever you die, I will die, and there I will be buried. May the Lord punish me severely if I allow anything but death to separate us!” 18 When Naomi saw that Ruth was determined to go with her, she said nothing more.

Commentary:

- The Divergence (v. 14): Orpah does the sensible, culturally expected thing. She returns to her people and her gods (Chemosh). Ruth does the unexpected, covenantal thing.

- Clinging (v. 14): The Hebrew word for “clung” (dabaq) is the same word used in Genesis 2:24 describing a husband joining his wife. It implies an inseparable, adhesive bond.

- Ruth’s Conversion (v. 16): Ruth’s vow is one of the most comprehensive statements of commitment in the Bible. It involves a total transfer of allegiance:

- Covenant Curse (v. 17): Ruth invokes Yahweh’s personal name in a curse formula (“May the Lord punish me…”), binding herself to the God of Israel under penalty of death.

- Hesed in Action (v. 16-17): Ruth exemplifies hesed—loyal love that goes beyond legal duty. She binds herself to a destitute widow who offers her no future prospects.

Insight: True faith is often demonstrated by costly loyalty. Ruth chooses the unknown with God over the familiar with idols.

4. Arrival in Bethlehem: “Call Me Mara” (Ruth 1:19–22 NLT)

19 So the two of them continued on their journey until they came to Bethlehem. When they arrived in Bethlehem, the entire town was excited by their arrival. “Is it really Naomi?” the women asked. 20 “Don’t call me Naomi,” she told them. “Call me Mara, for the Almighty has made life very bitter for me. 21 I went away full, but the Lord has brought me home empty. Why call me Naomi when the Lord has caused me to suffer and the Almighty has sent such tragedy upon me?” 22 So Naomi returned from Moab, accompanied by her daughter-in-law Ruth, the young Moabite woman. They arrived in Bethlehem in late spring, at the beginning of the barley harvest.

Commentary:

- The Commotion (v. 19): The town is abuzz (“excited”), likely because Naomi looks drastically different—aged by grief and poverty—compared to when she left as a wealthy noblewoman.

- Name Change (v. 20): Naomi changes her name to match her reality. “Naomi” (Pleasant) becomes “Mara” (Bitter). This reflects deep spiritual depression.

- The Almighty (v. 20): She uses the title Shaddai (Almighty), emphasizing God’s overpowering might, which she feels has crushed her.

- Theology of Emptiness (v. 21): Naomi claims, “I went away full, but the Lord has brought me home empty.” This is technically true regarding her family, but ironically false regarding Ruth. She is so consumed by what she lost that she cannot see the faithful companion standing right beside her.

- The Narrative Hook (v. 22): The chapter ends with a glimmer of hope: “the beginning of the barley harvest.” This signals that while Naomi feels empty, God’s provision is already beginning.

Insight: We often evaluate our lives by what is missing rather than what remains. Naomi felt empty, but she returned with Ruth—who would become the grandmother of King David and an ancestor of Jesus.

Theological Significance of Ruth 1

- Sovereignty and Providence: The chapter demonstrates that God is active not just in miracles, but in the mundane and the tragic. He uses famine, death, and human decisions to position people for His redemptive plan.

- Hesed (Loyal Love): Ruth introduces the concept of hesed—a key OT theme describing God’s covenant love. Ruth reflects God’s character by loving the unlovable and staying when she could leave.

- Inclusion of Gentiles: Ruth, a Moabitess (forbidden from the assembly in Deut 23:3), is brought into the fold of Israel, foreshadowing the universal scope of the Gospel where faith supersedes ethnicity.

- The Emptiness Before Fullness: The narrative structure establishes a trajectory from emptiness (famine, death, barrenness) to fullness (harvest, marriage, birth), mirroring the spiritual journey of redemption.

Practical Applications

- Trust in the Dark: Like Naomi, we may feel God is against us when things go wrong. We must learn to trust His character even when we cannot trace His hand.

- The Power of Commitment: Ruth’s vow challenges the modern consumer approach to relationships. True love says, “I am with you,” even when there is no benefit to self.

- Honesty in Lament: It is permissible to be honest with God about our pain. Naomi did not sugarcoat her bitterness, and her honest lament is recorded in Scripture.

- Look for the “Barley Harvest”: Even in our deepest grief, God often provides a small sign of hope. We must open our eyes to the new seasons God is bringing.

Final Insight

Ruth 1 portrays the collision of human despair and divine providence. While Naomi sees only the bitterness of the past, God is already coordinating a future that will lead to the King of Israel and the Savior of the world. The chapter invites us to believe that our “emptiness” is simply the canvas upon which God paints His grace.

Leave a Reply